The British Government, in 1838, passed an Act of Parliament aimed at abolishing Slave Trade in Africa. For that purpose, a steam-boat, named ‘Albert,’ was fitted for the voyage; and it set sail in 1841 under the Command of Captain H. D. Trotter. Other Commissioners were Captain William Allen, who was on the previous 1832 Richard Lander-led expedition, Captain T. R. H. Thompson, M.D. Surgeon, both of the Royal Navy. Rev. (later, Bishop) Samuel Ajayi Crowther and William Johnson both Yoruba and Igala former slaves rescued and trained as missionaries. The latter, whose origin was traced to the Ájú Akwù ruling house at Ida, served as the Interpreter during the Commissioners’ Conference with Àtá Àámẹ́ Òchéje.

Specifically, the mission of the 1841 expedition was “to ascend the River Niger and enter into commercial relations with the Chiefs and Powers on its banks, within whose dominions the internal Slave Trade of Africa is carried on, and the external Slave Trade supplied with its victims.” Following its execution, the expedition’s Narrative was written by Captain William Allen, who was a gifted artist who captured several scenes during the visit at Ida.

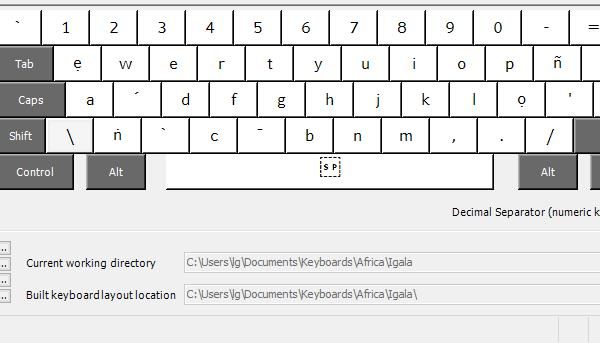

In this post, which is the beginning of a series, Ki-gala.com will be highlighting exciting historical anecdotes from the Narratives on the three expeditions, including the last one undertaken under the command of Captain William Balfur-Baikie in 1854. The posts will capture and reproduce the exciting moments of the voyages while also drawing attention to certain misconceptions and negative fixations regarding Africa as exhibited by the authors, whilst clearing the air on such circumstances.

Àbọkọ̀ Òchéje’s Show of Love to the Lander Brothers

African pupils who attended school in the 1950s through to the 1970s were, no doubt, familiar with the story of “The Lander Brothers” (Richard and John Lander) who were commissioned by the British Government, under the flying seal of Her Majesty the Queen, to explore the River Niger in Africa. Specifically, Richard, accompanied by his brother, was “to proceed to Africa for the purpose of ascertaining the course of the Great River, to follow its course, if possible, to its termination, wherever that may be.”

In a passage, titled: “The Richard Lander Story,” obtained from the Richard Lander Society’s website, details of the two brothers’ suffering during their (first) exploratory journey are revealed. On their arrival in Badagry, in what is now Southwest Nigeria, on 22nd March, 1830, they “were forced by the king of that town to drink poison” but they were lucky to escape by whiskers, as the king, on the spur of the moment, dismissed them, ordering them to proceed to the interior. From there, they “trekked five hundred miles inland to Yauri, where the Sultan there kept them hostage for five weeks.” Then, they travelled inland to Bussa, in today’s Niger State and explored the Niger for 100 miles (160km). From there, they began “a hazardous canoe trip down the Niger towards the river’s delta. While en route, they arrived Adamugwu – a major coastal town (now extinct) on the southern fringe of the Àtá-Igala’s territory, where fate brought them in contact with Chief Àbọkọ̀ Òchéje, the titled “Captain of the Port,” who manages the affairs of the River Niger in the Ida front up to its downstream boundary, north of Onitsha.

According to Allen, Àbọkọ̀ Òchéje showed demonstrable kindness to the Lander Brothers in their moment of need, “when the brothers landed at his town on their adventurous voyage down the river in a canoe. They were then in a destitute condition, and received much disinterested hospitality from the old chief. On the second, Lander had an opportunity of rewarding him handsomely.” On this current, 1841 voyage, however, William Allen “regretted to find, on inquiry, that this magnificent old man had been dead some years.”

Can a Possible Strategic Partnership Evolve?

This post emphasizes how Nigeria and Britain were brought together by their two historical figures, on the one hand, and Igala’s proverbial goodwill and hospitality symbolized by the persona of Chief Àbọkọ̀ Òchéje, on the other. It is hereby suggested that the Landers-Àbọkọ̀ relationship, which commenced nearly two hundred years ago, be revived and energized through economic cooperation. In particular, one may wish to call on the Richard Lander Society to, in conjunction with the British Government, actualize Sir Richard Lander’s dream project of converting the swathe of land “between the landing-place and a long, low island, which Lander had purchased from the King (Ata) and named ‘English Island,’ on which he had intended to establish a factory (p. 211). The Commissioners, during the Conference with the Igala Priest-King, had requested for “a large tract of land, to be purchased at Addakudda (Igbobe area) to make a farm there to show them how to grow indigo and cotton properly.” This last request was premised on the pre-voyage proposal initiated by The British Agricultural Society for the establishment of “a Model Farm on the banks of the Niger” (p. 230).

Igala played a very vital role in the emergence of modern Nigeria. This fact should be brought to the fore and to the knowledge of our government for adequate compensation and reward by developing Igala land and appointing our people to government positions.

I learnt that offspring of the Lander Brothers visited Nigeria and the Confluence area, in recent time. Did they make contact with the Abo’ko?